✈️ In praise of aviation

The trip economy at global scale demonstrates a safer and more equitable model than car ownership

You’re reading the RedBlue Newsletter, which offers deep takes on the intersections between mobility and technology. You can subscribe here:

Let’s imagine aviation worked like car ownership. The only way to fly is in a private plane. Since flying is useful for trade and business, the government offers tax incentives for owning a plane and uses property taxes to fund airports and swathes of hanger space needed when private planes are not in use. The planes themselves are cheaper to be more affordable for individuals, but also lower quality and less reliable. To make flying more accessible, flight training is relatively straightforward; the high rate of crashes is an unfortunate but unavoidable consequence. If you need to fly but can’t afford to own a plane, you can hitch a ride with a friend - if you have the right friends.

Mapping this analogy is tricky because it seems so absurd compared to the obvious logic of today’s commercial aviation industry. Flying is cheap, safe and reliable. A mile of flying costs less than half the price of a mile of driving. That same mile is also 60x safer to fly than to drive. Sure there are important differences between cars and planes - for starters a Gulfstream costs 300x more than a Model S - but that doesn’t change the fact that the business model supporting planes has numerous advantages over vehicle ownership.

Flying is the trip economy at scale: a transportation marketplace that sells standalone rides. Purchasing trips frequently — rather than vehicles infrequently — allows for more economies of scale, more sustainable infrastructure, and more efficiency. Trip marketplaces seamlessly match buyers and sellers, and generate competition to lower costs and improve quality. On the ground, similarly structured trip marketplaces - transit, ridehailing, and delivery services - are frequently safer, greener and more efficient than those based on car ownership. This feels paradoxical since once you own a vehicle, incremental trips feel cheap, but the price of access is high and the overall system is far less efficient. Aviation is a great example of how trip marketplaces combine affordability with comfort and has lessons that are transferrable to other forms of transportation that are hiding in plane sight.

To better understand the power of the aviation trip economy in action and how it makes for a more efficient, more comfortable and more scalable system, let’s explore three aspects of this industry that are not obvious on the surface, but have magical effects when combined.

1. A Theseus’ Ship of the skies ⛵

Southwest Airlines emerged and surged to prominence in the 1970s as aviation was being deregulated. Southwest found ways to turn around planes in very short periods of time (often in less than 15 minutes) while charging dramatically less. These innovations increased both the time planes spent in the air and the utilization of seats while flying.

The Southwest model is emblematic of a broader trend in the industry: a trip marketplace pushes towards maximizing asset utilization. Planes are in use more than 40% of the time, a rate ten times higher than cars. It helps that these assets are mobile - if a particular travel corridor sees a surge or slump in passengers, routes can quickly be adjusted to better satisfy demand.

Much like the ancient Athenians maintained the Ship of Theseus, replacing each plank as it decayed, airlines are constantly maintaining, upgrading and replacing portions of a plane at the rates they are worn down - from the coat of paint on the exterior to the seats inside. This replacement cycle is a hallmark of the trip economy. It feeds back into how manufacturers build planes: at high levels of quality to endure constant use over a long period of time and modularly to allow subcomponents to be replaced and upgraded over time. And it feeds forward into how these assets are operated, financed and maintain residual value.

Jet engines are especially Thesean and the benefits are immense. Manufacturers like Rolls-Royce have developed a unique business model that couples sales with “power-by-the-hour” charges: airlines pay an hourly rate for the engine-maker to ensure the engine is functioning well. This aligns incentives: airlines want their planes to have functioning engines whenever they fly and manufacturers are compensated for ensuring this. This model also allows manufacturers to gather data and insights about how well their engines are performing, creating a positive feedback loop.

Even though planes are expensive to finance and operate, the dynamics of the flight trip marketplace squeeze out maximal utilization and ensures affordable costs to consumers.

2. Disneyland with a jet bridge 🧚

When assets are used efficiently in a trip marketplace, more consumers can benefit. But there are additional ways to increase consumer surplus. Trip marketplace offerings invite bundling: flights and airports are combined with optional premium experiences that entice the wealthy while making these services more affordable for everyone else. It might be a bit jarring to compare a terminal to a theme park; if you’ve ever slept in an airport, your experience is unlikely to compare to the Magic Kingdom. But there are some fascinating parallels.

Airports - like Disneyland - are weirdly disassociated from the physical world that surrounds them. The liminal nature of airport terminals - nestled between international borders - is the foundation of duty free. The first version, improbably, was created for the rich and famous transiting through Shannon, Ireland. Before jet engines, planes flying transatlantic needed a place to refuel and the west coast of Ireland was closer to North America than England.

The duty free segment, which sells high end products like spirits and perfume (dominated by LVMH-owned DFS) served as the blueprint for what came next. Airports have evolved into luxury malls with global brands vying for the vacant hours of the iPhone-class travelers passing through on their way to the rest of the world. Even those not spending on high end retail benefit from high quality amenities and things to do during the time they spend waiting between flights.

Much like Disneyland, airports and airlines have succeeded in creating happy prisoners that can be better monetized.

Dior perfume is sold alongside Turkish delight in Istanbul and Gouda cheese in Amsterdam. Airports are emblems of and gateways to the nations that host them, making them eager to help support the airport bundle. Terminals may have less charm than Disneyland but have been expanded much more aggressively. Singapore and Dubai have been built on the back of airlines centered around a hub airport, and Saudi Arabia is attempting to do something similar with Riyadh Air.

But it is airlines that are the true masters of bundling. They have their own version of Disney Dollars: Miles. Miles are the ultimate embodiment of a loyalty bundle. Miles grant access to lounges, upgrades, shorter queues, and better experiences. Airlines bundle liquor and status with their hub airports to entice travelers to pass through them. Increasingly airlines are using miles as a currency for retail within a captive terminal - such as United’s Terminal C at Newark where you can purchase food with them. And miles extend into a broader bundled ecosystem of travel and retail experiences: credit cards, hotel bookings and car rentals.

Planes have even more captive power than terminals. Seat pricing is the most powerful way in which bundles are used to capture value from those willing to spend while affording an adequate service to everyone else. Getting from point A to point B is essentially a commodity, but when traveling a long distance locked in a plane, small differences - food, comfort, a warm scented hand towel - are worth a lot. This is especially true for employees traveling for work, with an employer that is less cost sensitive than they would be if they were covering the fare themselves.

It took airlines a while to figure out price segmentation, but it allows them to offer comfort to those who can afford it and affordability to those who need it.

3. The invisible hand 🙌

A trip marketplace shines a bright light on the companies that operate within it. When big companies are responsible for large numbers of trips, policymakers get easy access to levers for better social outcomes. This has a major impact on safety. Considering how much can go wrong while flying, it’s astounding that it so rarely does. In the US last year, just 11 people died in plane crashes. In 2021, no one did. That’s in contrast to 31,850 that died in car crashes that year. What’s more, safety for the two modes are trending in opposite directions - cars are getting more dangerous and flying has been getting safer.

Flying used to be dangerous, but because every major incident is reported and investigated, lessons are learnt and systems are improved. A standardized set of guidelines for operation and maintenance makes flying planes safer - those that adhere to it have significantly lower incident rates. Meanwhile, a database that allows air and ground crews as well as air traffic controllers to report incidents anonymously helps catch problems before they escalate.

The airline industry’s obsession with safety can be a little overbearing—like when you’re told to push your bag under your window seat or forced to close your laptop during takeoff—but puts in stark contrast how lax our approach to road fatalities is.

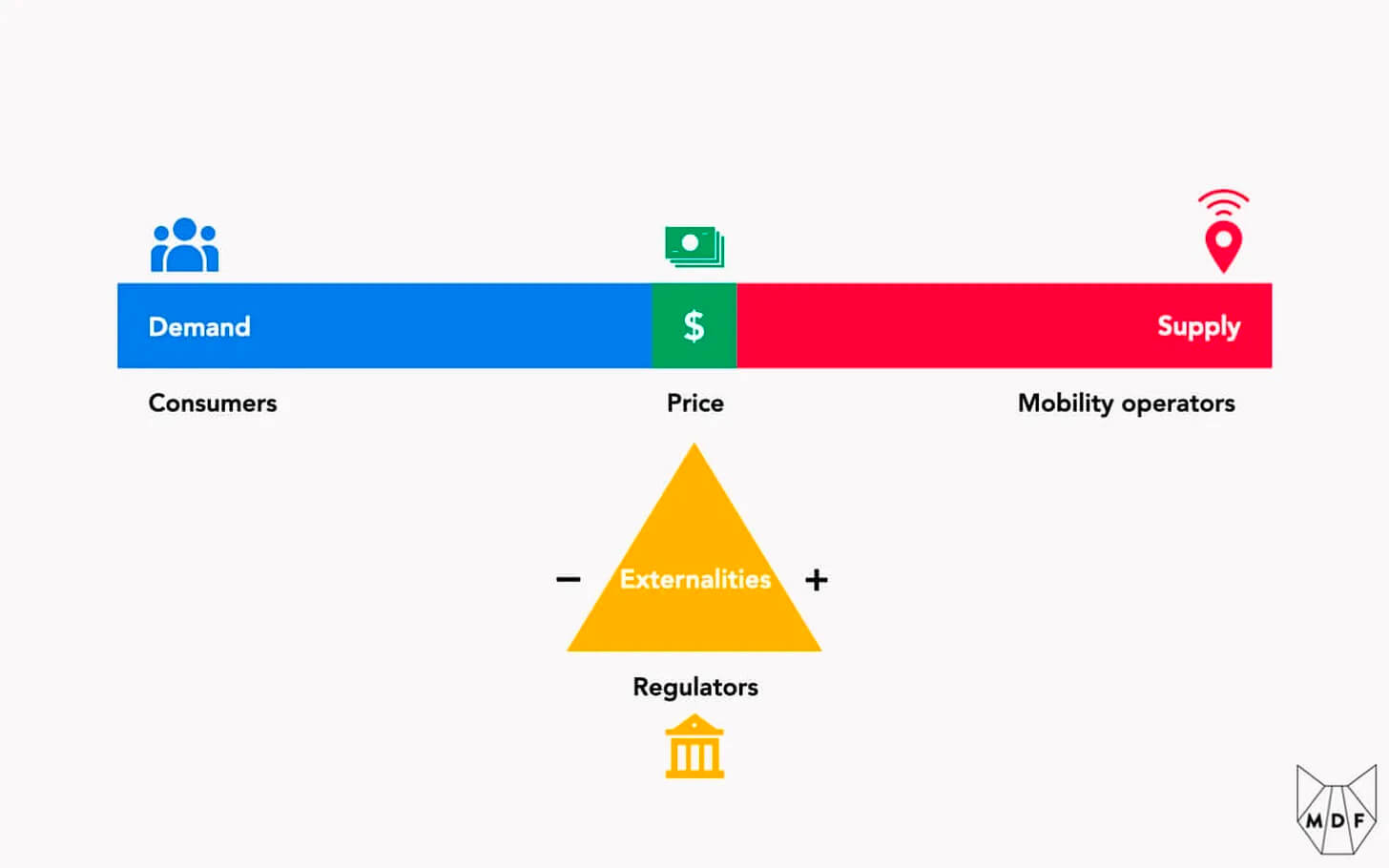

Beyond the generally constructive attention to safety that comes with a massive, centralized marketplace, the trip economy also gives regulators powerful tools to address externalities by factoring them into pricing. I call this the trip triangle. It offers an elegant way to discourage bad outcomes and encourage good ones while creating very little friction in the system since the externalities are wrapped into individual trip prices.

Here are some of the externalities that are bundled into the price of flying, mostly invisible to consumers:

To be clear, the ease with which costs can be added to trip prices introduces the risk of mission creep - and indeed costs have grown since airlines were deregulated in the 70s. But it is still a great way to pay for new infrastructure like airport terminals. It allowed a simple way to improve security in the wake of 9/11 (even though there is a lot to criticize about the TSA and its security theater). Flying depends on airport operations like air traffic control - and these are easily built into fares. And since they are accountable for each trip, trip pricing also means that airlines can be made to pay fees when they leave us waiting or stranded.

It’s helpful to compare this with how we pay for ground transportation. Parking is bundled into the cost of real estate and paid for even by those who don’t drive. Meanwhile, the gas tax no longer pays for the infrastructure it is intended to support as vehicles have become more efficient and we transition to electric vehicles. The ownership economy makes it much harder to align incentives and externalities.

View from above 🛬

Looking down from the portal view of an airplane as it comes in to land, you can see the blinking lights of houses and office blocks, and cars moving between them.

The big difference between these two systems is business model. Aviation works within the structure of a trip economy, where consumers pay for individual journeys and a marketplace creates intense competition to improve asset utilization and customer experience while externalities are easily priced into the cost of trips. Meanwhile cars are tied to an ownership economy in which vehicles are used a tenth as much as airplanes and remain unaffordable for many Americans, locking them out of the engine of upward mobility and exacerbating inequality.

Those who can afford the convenience of a private jet can still own one - it’s just absurd to imagine the government subsidizing it. We should channel that intuition into asking whether it makes sense to channel massive subsidies into car ownership and free parking, simply because it mostly benefits the middle class instead of the rich.

Not every lesson is portable across these systems, but it is worth considering why one seems to work so much better than the other and how we can bring the benefits of the trip economy back down to earth.

Love this article....

Both my parents were airline crew and as an airline brat I always get fascinated by how the industry both helps and harms our planet.... Finding the right balance that reduces that harm is always key.

BTW I am old enough to remember people smoking onboard the plane, constantly.... thank god that stopped!

Love

G @ ENSO

You left out one huge elephant in the room.

We hate flying, at least in coach. All of us. Flying in first class isn't too bad, but it still has many of the attributes that we hate about flying, in particular the airport that has turned into a shopping mall with occasional planes attached. Which you view as good, somehow.

We hate it so much people routinely drive from San Francisco to LA -- 6-7 hours -- rather than the 50 minute flight that takes 3 hours by the time you are done. In Europe they prefer the train even when slower over similar distances.

So sure, it's optimized and safer. Yes, it costs a bit less per mile than driving if you drive alone (if two travel it's not so much a win especially if you have an electric car and you want a car at your destination.) But it's miserable. Horrible airports that are getting worse. They just replaced the best airport terminals I have seen in Kansas city, where it was literally a 100 foot walk from the door of the plane to your taxi, with a modern monstrosity.

Fly private of course, and most of this goes away, at a ridiculous price.

I make Utopian predictions for the robotaxi world. In particular a world where, when a few people are all taking the same trip at the same time, they are naturally pooled together to get all those efficiencies, but when they are not doing that, they can travel in private with no compromises of their trip except the congestion we get because the roads are a commons (a mistake we could, in theory, fix.)

Yes, for more than 200 miles we're still going to fly, but we're not going to praise it. We will do it because it's the only choice.

...Back to your love of airports. Today's airports make more money from store rents, parking and ground transport fees than they do in passengers fees for that minor side-business known as flying. This has warped their design. Now get through security and it's a gauntlet of perfume and then what can be a 20 minute walk to a gate. Airports imagine they are places to hang around. Train stations do not, they are functional, get through and get on the train. Ditto car parks. Airports make it deliberately harder to get to your Uber (or transit.) They have become like the Las Vegas hotel which makes sure you go through the casino to get anything.

There is a classic dilemma in transportation. Travel together can be more efficient. But the more people you bunch together, the more compromise each must make in terms of route, departure times, comfort and much more. As the vehicle grows the compromise gets so high that people move to better, much more expensive modes. They pay 10x as much to have a private car, 100x to have a private plane. This is why the A380 died -- it was too large to be efficient. Read that phrase again ... "too large to be efficient." Few in transportation understand the need for a happy medium.