Realizing generalizable robotics

This post can also be read on our website

Before AI can take over the world, it needs a robot army. And in order to build a robot army, it needs robot factories. Which makes robotics pretty important to the future of AI.

While some AI predictions have proven hyperbolic, the question of how to make robotics more generalizable is a natural outgrowth of the rapid improvement in large language models (LLMs).

We are still a long way from robot armies. Robots today are impressive, but but only when doing a narrow task.

General purpose robotics (Gen-P) is an attempt to change that, and do for robots what LLMs did for software: move from narrow, hand-crafted behavior to systems that generalize. By “Gen-P” we mean robots that can adapt across tasks and environments with minimal task-specific programming or retraining.

In this essay, we examine how the lessons from LLMs are shaping the emerging Gen-P stack, why generalization in the physical world is fundamentally harder than in software, and the two primary paths companies are taking to build generalizable robotics systems. We then explore what this means for commercialization, investment and where durable value is most likely to emerge as robotics moves from impressive demos to systems that work reliably in the real world.

🐚 Cambrian explosion

Robotics has been an important investment category for years, but the last few have brought a sharp influx of capital into the new class of Gen-P startups.

The shift is visible in the funding numbers. Billions have flown into this space in just a few years, with more than 150% YoY growth this year alone.

Capital is concentrating around the companies seen as early leaders, including Figure AI, Skild AI, Field AI and Physical Intelligence, each of which has raised mega-rounds at multibillion-dollar valuations. At the same time, a wave of newer entrants is raising aggressively to close the gap, like Generalist, Dyna, Genesis AI and Persona AI.

🌐 The Digital Precedent: Lessons from LLMs

The LLM playbook in the digital “world of bits” is the benchmark for what investors hope to achieve in the physical “world of atoms” with Gen-P, so outlining the LLM stack and key developments is a helpful starting point.

At the foundation layer, a general-purpose model is trained by scaling data and compute.

At the application layer, that base model is adapted into an assistant using Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and other algorithms (e.g., fine-tuning, architecture choices, reasoning scaffolds) to make it more reliable and aligned.

At the distribution layer, users access the system through interfaces (apps/web) or APIs, which produce feedback (prompts, completions, ratings, outcomes) that is collected and incorporated later into new training runs—improving the next version rather than updating the deployed model in real time.

Foundation - scale (data + compute) beat cleverness: Rich Sutton’s “Bitter Lesson“ held true. Massive compute and data (increasingly synthetic) has driven LLM performance and fueled an data center arms race to build better foundation models

Application - algorithms have turned raw power into usable assistants: Techniques like RLHF, more efficient architectures (e.g. mixture of experts (MoE)), and “System 2” reasoning models (o1-style) transformed scaled models from chaotic engines into aligned, step-by-step thinkers. The resulting application layer models can be applied to solve a broad set of problems

Distribution - value is shifting from models to workflows/specialization: Foundation models are becoming utilities under price and open-source pressure, while durable value accrues to specialized applications that own workflows, data and customer relationships

Feedback - digital AI is general but not adaptive in the wild: LLMs can handle a wide range of tasks zero-shot, but once deployed they do not learn from their mistakes. User interactions don’t update the model in real time; meaningful learning still happens offline through reinforcement learning or fine-tuning or through selecting particular types of training data to improve the next generation of foundation models.

🍎 AI meets physical: The Gen-P robotics stack

The rapid evolution of LLMs deeply shapes intuitions and architectures for generalizable robotics. A Gen-P stack is emerging which is similar to that for LLMs, but with some important differences. Critically, in contrast to LLMs, which primarily understand and generate output in the form of language, generalizable robotics must understand and interact with the physical world.

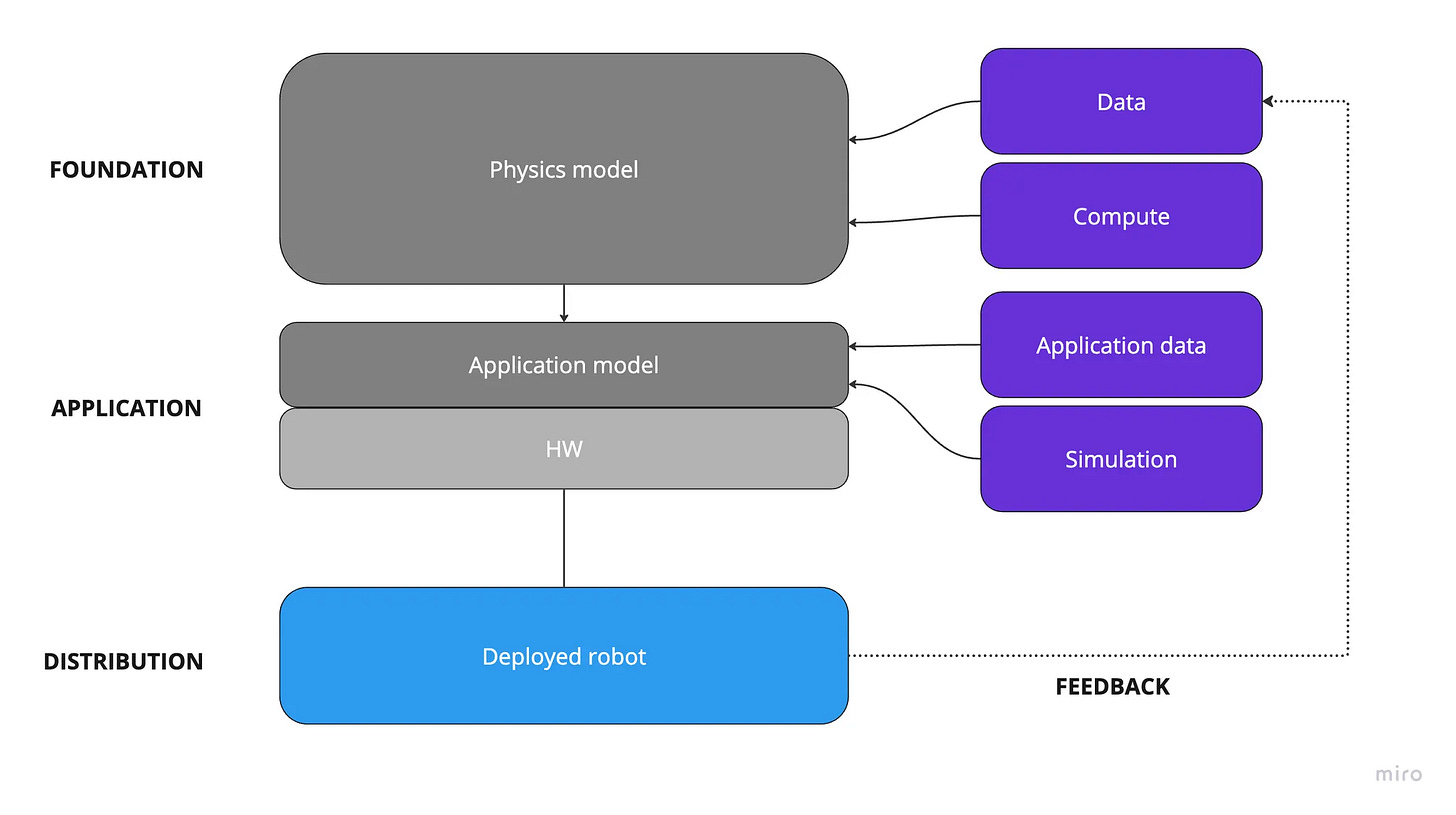

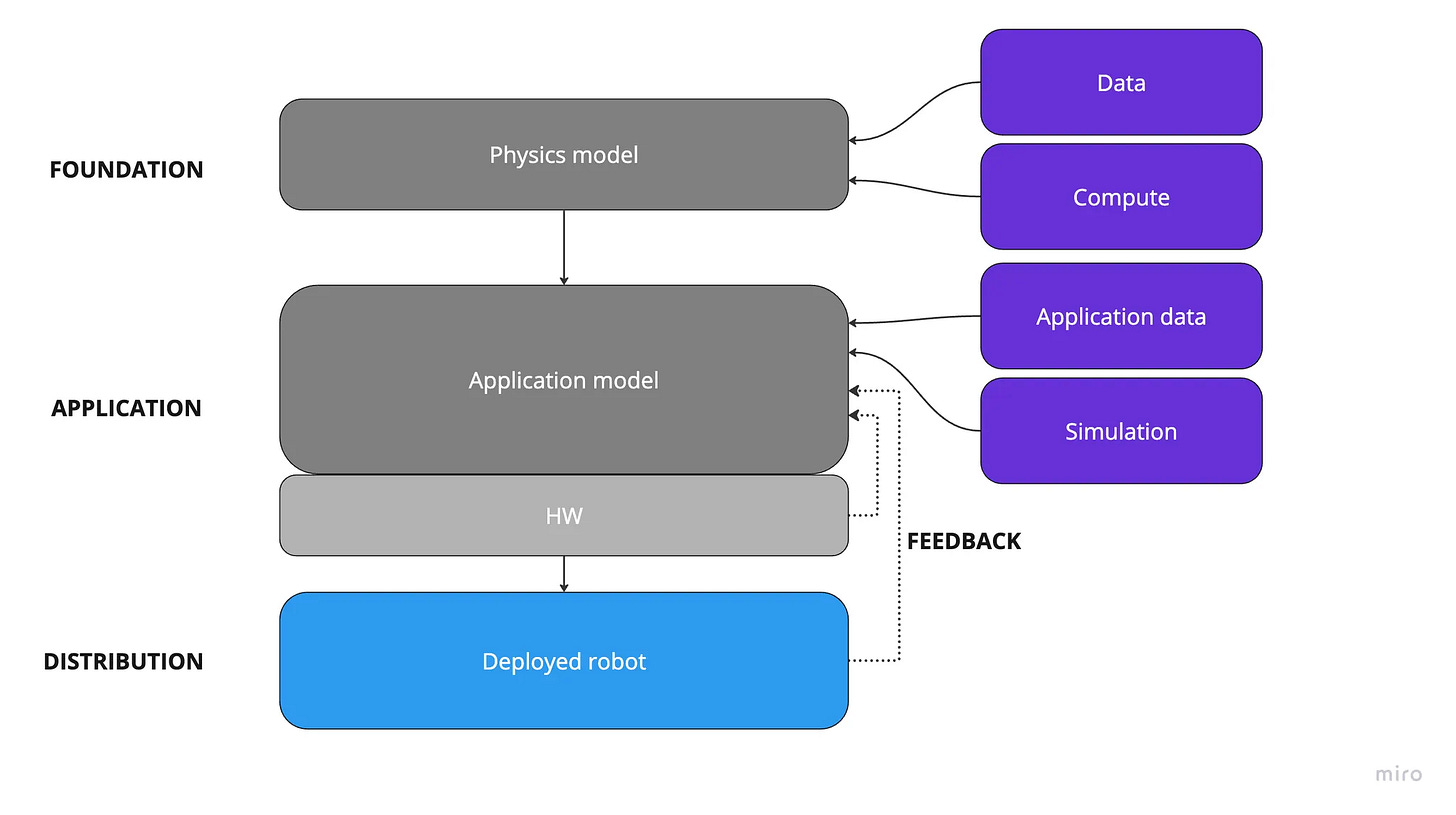

At the foundation layer, a physics model is trained with data (sensor streams: vision, depth, proprioception, force/torque, etc.) and compute to predict contact, forces, object motion and the outcomes of candidate actions (i.e., a learned intuition for how the world responds).

At the application layer, that physics model is combined with hardware (HW) constraints like embodiment, sensors, actuators and end-effectors, into an application model that turns perception into motor commands for a specific robot. The application model is improved using application data (task- and environment-specific logs, demos and outcomes) plus simulation (synthetic rollouts to scale training and testing).

At the distribution layer, capability ships as a deployed robot operating in real environments, where performance and edge cases generate the next round of data for offline model updates.

Physics Model (data + compute)

Data is also the foundation of Gen-P robotics and combines with compute to create a model of the physical world. This physics model takes in sensor data such as images, depth, joint positions, etc., and predicts contact, force, object motion and the consequences of a proposed action. In effect, it provides the robot with a learned intuition about how to interact with objects: how hard to grip, how far to push, when friction will and won’t hold, and which actions are feasible given its embodiment.

Unlike language, there is no internet-scale corpus of physical interaction - this new data needs to be generated and collected, making it the core bottleneck.

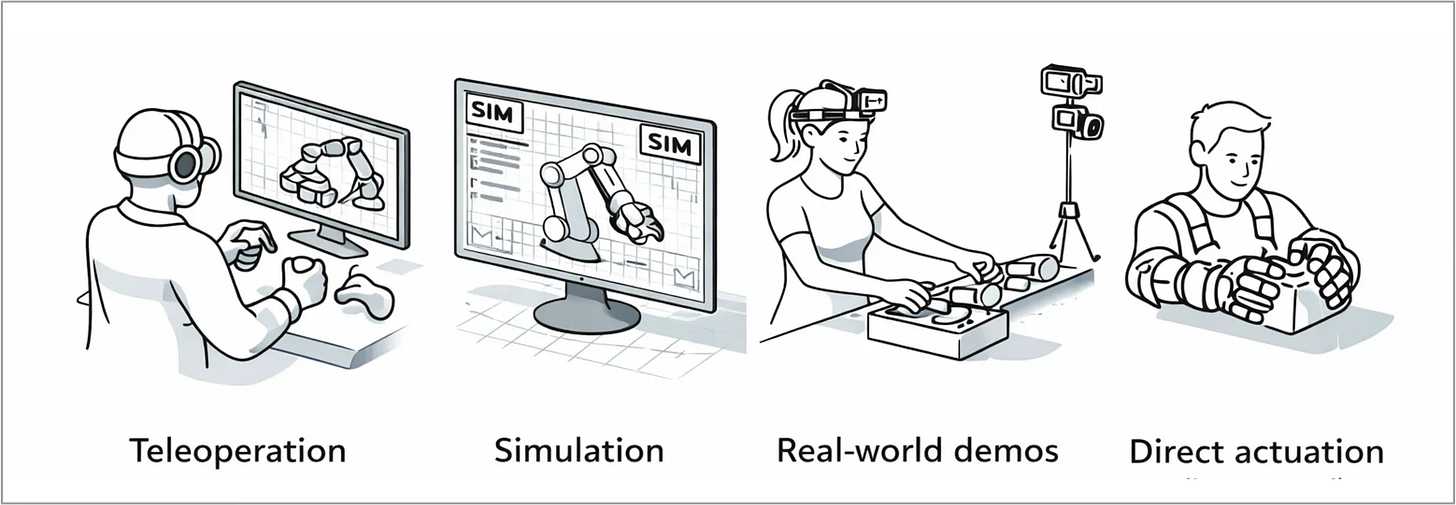

There are four main approaches to collecting this data that feed into the physics model:

Teleoperation: humans remotely operate robots to collect demonstrations; mostly high-quality but slow, and sensitive to hardware mismatches, latency and poor force feedback

Simulation: synthetic data from physics engines; easy to scale and good for locomotion/coarse skills, but weak for fine manipulation, friction and deformables (e.g. soft/cloth-like objects whose shape changes)

Real-world demos: human videos or motion-capture rigs (e.g. body cam), plus logs from deployed robots; rich strategies and context, but often mismatched to robot embodiments

Direct actuation: humans wear kinematically matched end-effectors with the robot’s own sensors. Rigs can be used anywhere or directly on the production line itself, allowing data to be collected in the exact environments where robots will eventually operate. This produces diverse real-world data consistent with a robot’s action and sensing parameters

Application Model (physics model + HW)

An LLM has no body; its “body” is the command line. A robot has a specific physical form. Because of this, a physics model that can understands the physical world must still navigate the specific hardware constraints of the robot to achieve practical outcomes.

The application model is the layer through which these hardware constraints are intermediated - leveraging specific sensor input to understand the scene and actuate motors to move the robot or its end effectors to create particular outcomes.

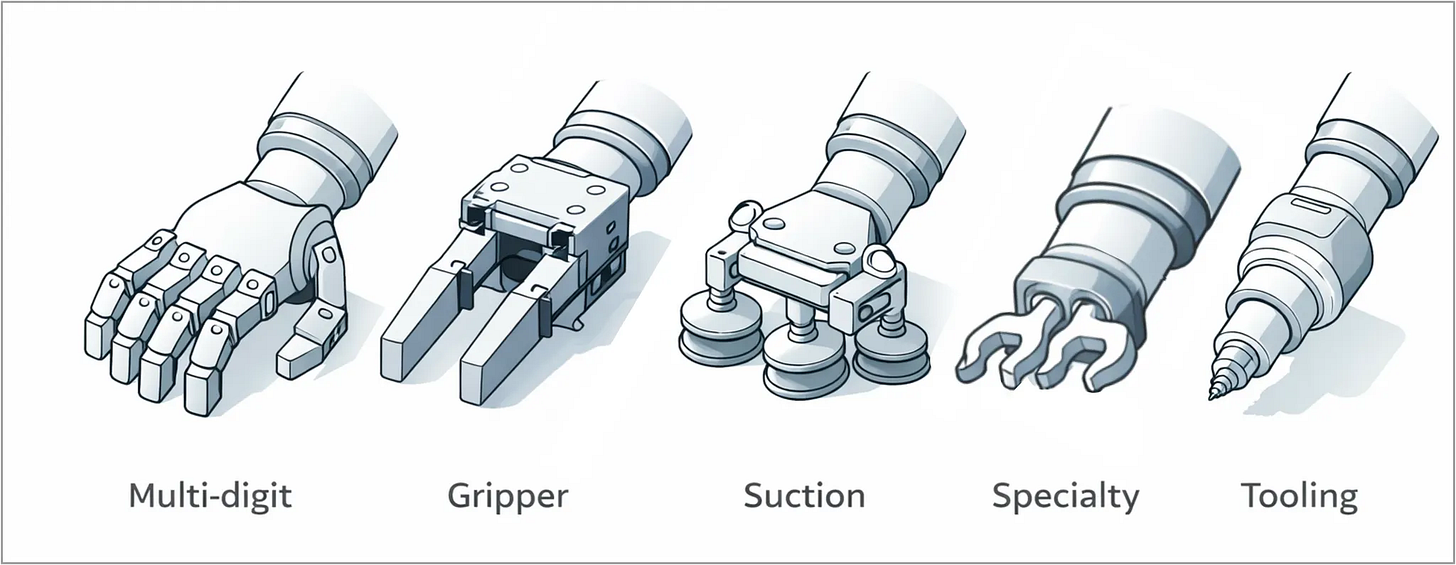

On the level of hardware, important choices need to be made in order to allow the robot to perform certain functions. One of the most critical choices on the hardware level is that of the end-effector, the part of the robot that most directly interfaces with the physical world.

These are the key categories of end effectors, each with its own tradeoffs:

Multi-digit: Hand-like fingers for dexterous grasping, regrasping and manipulating irregular objects and tools; these are the closest analogy to human hands and are likely to have the greatest generalizability but are also more complex and expensive

Gripper: Mechanical pincers/jaws for robust, repeatable holding of parts across a wide range of shapes and weights

Suction cups: Vacuum-based picking for fast handling of flat, smooth, or sealed-surface items (often in high-throughput workflows)

Specialty handling: Specific shapes or properties (magnetic, electroadhesive, needle, hooks/forks, etc) for hard-to-grip materials and edge case manipulation; these end effectors solve fixturing and grasping problems when simple fingers or suction cups don’t work

Tooling: Task-performing end effectors (e.g., welding, fastening, dispensing, cutting, sanding, etc.) that act on the workpiece rather than just holding it; these end effectors perform a process on the workpiece rather than just performing grasping or manipulation

Depending on the distribution strategy, the physics and application models might be quite distinct, or more tightly integrated.

Distribution: The specificity of the physical world

Some aspects of the Gen-P stack (such as the physics model) are broadly generalizable, but a crucial difference to LLMs is that robotics applications must be scaled through hardware in the physical world, with direct implications for feedback loops and go-to-market strategies.

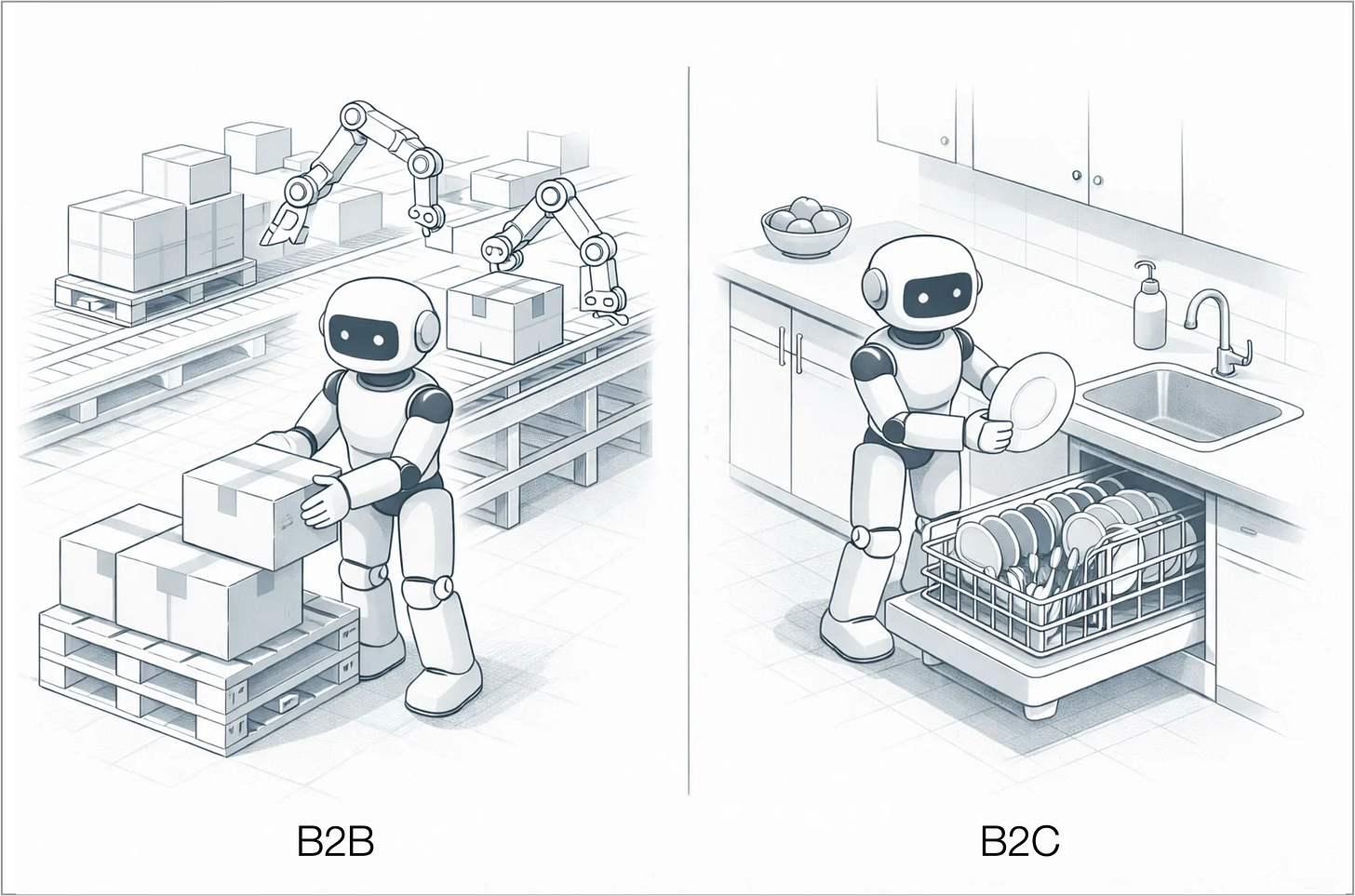

Broadly, there are two core areas in which general robotics can be deployed: B2B applications focused on business use cases, and B2C applications aimed at consumers.

B2B applications include production-line automation (case packing, palletizing/depalletizing, kitting, quality inspection), discrete task-focused workcells (machine tending, CNC loading/unloading, welding, sorting) and delivery or handling systems in warehouses and factories. Success in B2B is defined by hard return on investment (ROI) considerations: higher uptime, lower labor cost per unit, better safety and throughput, plus deep integration into existing workflows and IT systems. Differentiation comes from tight vertical focus, fast and reliable deployment, service and support and proprietary data loops in specific environments that make the system steadily better than generic competitors.

B2C applications center on the home: mobile robots that can load and unload dishwashers, tidy and move objects, assist with cooking and laundry, monitor safety, support seniors or people with disabilities, and eventually act as a general household assistant rather than a single-purpose appliance. Success in B2C depends less on formal ROI and more on trust, daily usefulness and emotional acceptance: the robot must be safe, intuitive, affordable and reliably remove real pain points from people’s lives. Differentiation comes from doing a few high-frequency, high-annoyance jobs extremely well, building an ecosystem around the device (apps, services, integrations) and compounding advantage through in-home data and brand loyalty.

🚪 The two paths to Gen-P

A crucial question sits at the core of Gen-P robotics: go wide or narrow?

There are two development paths that are being pursued in parallel. One path resembles the ambition behind LLMs. The other extends the tradition of industrial automation. Each path reflects a different assumption about how generalization will emerge in the physical world, and each implies a different data strategy, deployment strategy and business model.

1. Broad loop generalizability

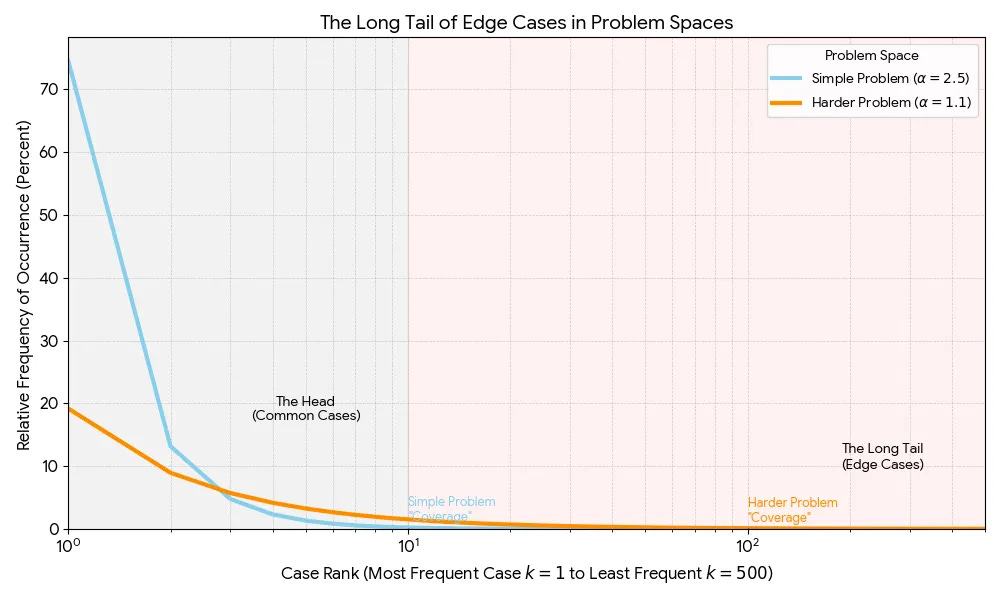

The first path focuses on addressing real-world complexity upstream at the level of the physics model. The end goal is a robot that can enter a new environment and solve a task it has never explicitly seen before. This is the zero-shot dream. It leans fully into the Bitter Lesson: if you can find a reliable gradient of improvement, you can justify extraordinary investment into scaling data collection and compute until the rare-but-important failures that dominate reliability (the so-called ”long tail of edge cases”) is compressed.

In the purest version of this approach, the application model largely collapses into the physics model. Task logic, planning and control are expected to emerge from a sufficiently powerful general model rather than from hand-built task layers. The “application” becomes a thin wrapper around a broad capability engine. More pragmatic versions still retain an application layer, but treat it as temporary scaffolding. As the physics model improves, more responsibility is pulled upstream and the application layer is expected to shrink over time.

The challenge is that the feedback loops are long. Large models must be trained on huge, diverse datasets, deployed into the world, observed failing in subtle ways, and then retrained with new data. Each iteration is expensive and slow, and progress is hard to measure until systems are tested in real environments. The potential payoff is enormous, but the timelines are uncertain and the difficulty of the long tail remains largely unmapped.

2. Narrow loop specialization

The second path takes a different approach to complexity, aiming to solve for it in context. This approach focuses on the application model, using it to train a specific end effector to complete specific tasks reliably. The hardware is closely scoped to the use case.

This is the continuation of the robotics playbook that has worked until now, but it rides the wave of improvements in physics models to solve an increasingly broad set of problem. However, core to this approach is the belief that production solutions involve complexity that require use-case specific data to solve for in order to create the kind of highly reliable solution needed in production. This path has a clear business model and commercial value. It leverages shorter feedback loops, but does not aim for a zero shot solution (i.e. works in a new task/environment without additional training). It trades ambition for pragmatism and optimization in terms of hardware with an optimal bill of materials (BoM) for the application it is tied to.

The ultimate goal is to expand into a diverse set of applications with generalizable capabilities, but arrives there through concrete problem solving rather than by leveraging massive models.

🤏 Crossing the uncanny valley

The two paths to Gen-P have distinct approaches to solving the long tail of complexity in the physical world. Broad loops assume that this complexity can be primarily solved for at the model level; narrow loops assume that this needs to be solved for through concrete deployments at the application and distribution level.

LLMs have become broadly generalizable through heavy investment in foundation models. Still there are questions about whether the current architectures can continue to generalize (Ilya Sustkever, for instance, thinks that LLMs are moving back into “the age of research”).The chart contrasts a simple domain (steep drop: most probability mass in a few common cases) with a hard domain (fat tail: many low-frequency cases still matter). Robotics lives closer to the long-tail regime: after about 80-90% coverage, progress slows because reliability depends on mastering a large number of rare, messy interactions rather than just improving performance on the common cases.

The critical question for robotics is how hard is it to solve for the long tail of complexity. Evolution spent about 500 million years getting animals to reliably perceive and act in the physical world, from early nervous systems to today’s exquisitely coordinated eyes, muscles and balance. By contrast, it’s had perhaps 2-3 million years to develop cognition in hominins, and less than 200,000 years for anything like modern language. We fixate on “intelligence” because it underwrites human supremacy and because motor control feels so “basic” we barely notice it. But that’s the uncanny part: what feels trivial to us is the product of immense evolutionary investment in solving an extraordinarily hard physical control problem.

The uncanny valley is the eerie zone where an AI system looks and moves almost, but not quite, human; close enough to trigger our social expectations but just different enough that every flaw feels disturbingly obvious. Gen-P lives in a similar uncanny valley of capability. Once robots can handle 80-90% of everyday situations, the remaining long tail of rare, messy edge cases becomes glaring, and truly “solving” Gen-P means systematically climbing out of that valley by mastering the hard residue of real-world complexity. Autonomous vehicles are a great example of hard this can be.

AVs: The long road to generalizability

The problem of the long tail of complexity in solving automation problems in the physical world is highlighted by the history of autonomous vehicles. All of Elon Musk’s predictions about robotaxis were wrong, as brutally chronicled by Bloomberg.

It is relatively easy to get an autonomous vehicle to drive well for a large percentage of the time, leading to impressive demos. Google’s car project (the predecessor to Waymo) was driving competently on highways in 2009. But it has taken 16 years to transform this technology into the production version that is ready to carry passengers on highways.

It is still hard for these vehicles to have a sufficiently sophisticated world model that can deal with every rare but risky situations, especially as deployments scale rapidly.

This Waymo doesn’t “understand” why this decision is dangerous:

Solving for autonomous vehicles is different to solving for robotics. In order to have a commercial robotaxi service that operates across a city with no human driver, you need to create a vehicle that can drive on every road in the city and negotiate almost every scenario that the vehicle will encounter, including frequent interactions with other drivers and pedestrians.

But driving has relatively few inputs - you can accelerate or break and turn the steering wheel left or right. In contrast, manipulation involves moving digits across many degrees of freedom and interacting with a wide array of objects in diverse environments which are less consistently structured and regulated than a city’s roads. Adding in locomotion for humanoid robots adds even more complexity to the equation.

It’s hard to extrapolate from these differences how relatively hard these two problems are, but it seems likely that it is harder to solve for Gen-P robotics than autonomous vehicles, and the time it has taken to get AVs from a promising demonstration to a level of maturity ready to scale offers some sense of the scale of the challenge.

TCO and ROI

The main constraint in scaling autonomous vehicles is not just autonomy, it’s economics. Robotaxi fleets only work if each vehicle stays highly utilized, and if the vehicles and sensor stacks get cheap enough to justify the service.

Robotics faces the same reality. In most B2B deployments, winners will be the teams that design the robot with the right hardware for the workflow, an optimized bill of materials (BoM), and reliability that makes the payback math obvious. Because these systems are physical and must be built, shipped, installed, and serviced, total cost of ownership (TCO) and return on investment (ROI) tend to dominate what looks like a purely technical problem.

Bifurcation of capital

Investment decisions in Gen-P robotics flow as much from investors’ theories of the future as from the constraints of their own fund models. Venture capital is increasingly bifurcated between mega-funds with massive pools of capital and lower, but more predictable return expectations and smaller funds which seek to capture outsized returns but put less capital to work in achieving them.

Broad-loop generalizability (Path 1) is structurally top-heavy in capital. These companies need to raise enormous sums up front to build data collection infrastructure, train large physics models, assemble world-class research teams and carry years of burn before achieving meaningful commercial traction. That makes them natural homes for very large pools of capital that need to write $100M+ checks into stories that can plausibly support tens of billions in outcome value.

Money here is not just fuel but a weapon: it buys talent, accelerates data and compute scale, lets companies acquire promising startups and subsidizes deployments to achieve distribution.

The risk is that the improvement curve is still unclear. We don’t yet know whether Gen-P is in an “era of scaling” or still in an “era of research,” and the true TAM is conceptually enormous but operationally vague. From an IRR perspective, these bets can be spectacular if the models keep improving and one or two winners emerge, but timelines and capital intensity also create significant challenges.

Narrow-loop specialization (Path 2) has almost the opposite capital profile. These companies can’t productively ingest unlimited capital. They are constrained by how fast they can stand up software stacks, qualify hardware, integrate with customer environments and scale service teams.

The upside to narrow-loop is a far clearer line of sight to ROI: specific use cases, defined hardware BoM, measurable payback periods and repeatable sales motions. This fits better with smaller, more focused funds and growth investors looking for strong unit economics, shorter feedback loops and the potential for attractive multiples on more modest check sizes. The upside may be capped relative to a true Gen-P platform, but the IRR can be excellent if teams compound across adjacent use cases and geographies, and it may be the only viable path to long-term scale.

Crucially, this is not necessarily an either/or world. Broad-loop players will need narrow-loop deployments to generate real data, revenue and credibility, while narrow-loop winners may eventually become acquisition targets or distribution partners for the largest platforms.

Our predictions

Durable funding: Gen-P is a huge opportunity space - the TAM is all of human physical labor - which will continue to attract significant investor interest for a sustained period of time provided there is evidence of improvement, much as we’ve seen with autonomous vehicles

There will be multiple types of winners: Given the size of the opportunity space, there are lots of discrete problems to be solved within both the Gen-P stack and at the application layer, with the potential to build many large businesses

TCO will matter at the application level: Application specific robots will have defensibility and earn customer lock-in if they can demonstrate reliability and optimize BoM

Specialization: The combination of the preceding points suggests that specialization will be rewarded (as we’re starting to see with LLMs) - winners will excel in particular areas, but will also need to achieve significant scale to be durable over time

Hype cycle: In spite of the opportunity’s scale, the realities of the physical world will prove a drag on the hyped-up demos as the long transition to systems that work reliably in context plays out, similar to AVs; along the way there will be bankruptcies, pull-backs and consolidation

Physics models are not the obvious bet they seem to be: Much like with foundation models, significant value will flow from physics models, but competition in this space will make this a very expensive game with the risk of commoditization to the benefit of the application layer (as we’re seeing with “wrapper” companies for LLMs)

Humanoids will be extra hard: Though the promise of humanoids is the greatest, they are trying to solve the hardest problem and will take a very long time to reach generalizability; there will be the greatest reset in this domain

Data strategies: Certain data collection and end effector approaches will prove more effective and the market will over time consolidate in these directions; companies that determine the best approach earlier will be advantaged

Commercialization will be the ultimate test: Venture capital will be able to bridge the gap between vision and reality, but commercial proof points will be critical to generating a durable funding advantage for winners, and real world monetization will be needed by the time that funding momentum subsides

RedBlue Capital is an early stage, thesis-driven venture capital firm focused on the transformation of the real economy inc

luding transportation, logistics, manufacturing and energy infrastructure.